Miscellaneous Archive

Here is the archive of past science snippets and physics posts... I hope they're of interest.

Science snippets

6. Caring for a new book

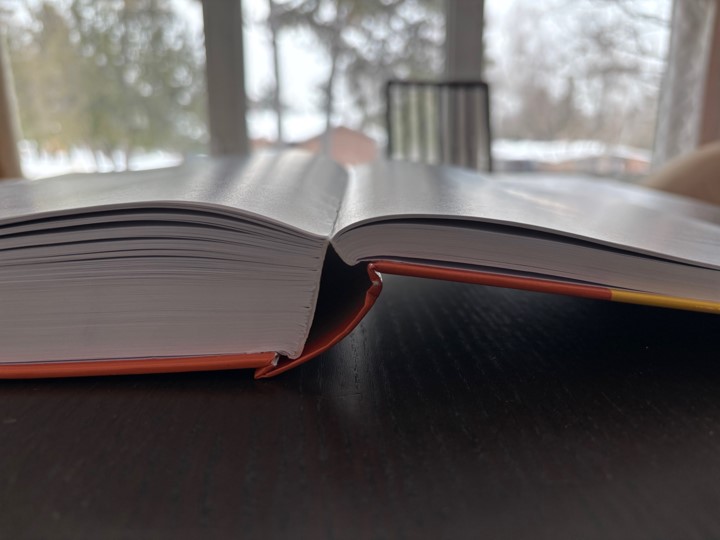

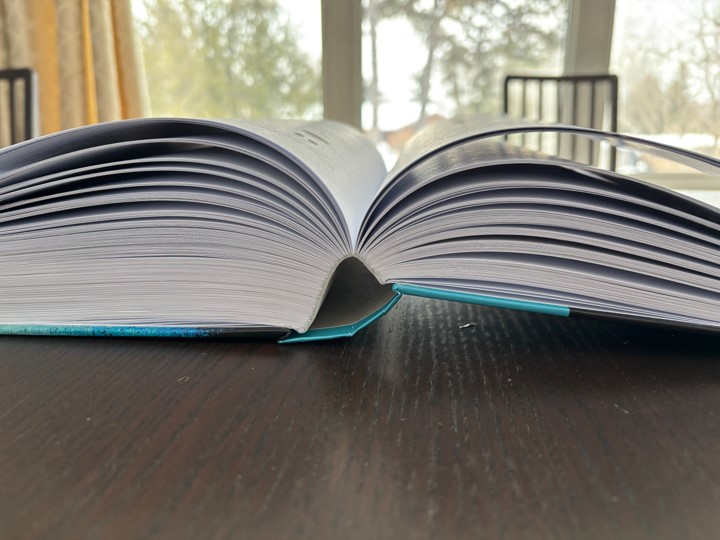

I recently encountered a trick to condition a new book to prevent the spine from cracking. This was sadly too late for one book (note the orange book below), but saved another (see the blue book). A cracked spine can cause pages to fall out, but if the spine bends instead of cracks then all is well. In mathematical terms we want the slope of the spine to remain continuous.

The process takes about ten minutes (less than the time spent reading a book!), and adopts the following approach:

-- Start with the book at room temperature or warmer, and before opening the book fully.

-- The general strategy is to place the book with its spine on a desk and gently push along the inside of the spine, with the spine kept concave as seen from below (check out the videos here and here).

-- I usually start near the middle of the book, with half the pages lying flat on the desk and the other half held about 45° above the horizonal. I then lift around five pages each time up from the horizontal, pushing along the inside of the spine until all the pages originally lying flat have been lifted.

-- I then repeat this for the other half of the book.

Now, enjoy!

5. The Earth is rotating a bit faster these days... reason(s) yet to be determined

The Earth rotates about its axis, with a period relative to the incoming Sun's rays of almost exactly 24 hours (86,400 seconds). Actually, being not totally rigid (it's made from solids, liquids, and gases which each deform due to internal stresses, weather effects, and the motion of the Moon) it rotates a little erratically. This plot from 2000 to the present day shows small daily and seasonal differences in the length of a day from exactly 86,400 seconds by about a millisecond or so. Besides these variations, for millennia the Earth has on average slowed down, with the average length of a day increasing by about 1.8 ms every century for the past few thousand years. We currently adjust for days having an average length greater than 86,400 seconds by occasionally adding a "leap second" to our clocks to keep them synchronized with dawn and dusk.

As the plot shows, however, between 2000-2005, and also since 2016, days have been on average (the black line) getting shorter, which means the Earth has been speeding up. Indeed, since 2020 the average length of a day is now less than 86,400 seconds, so we may soon need to subtract, rather than add, a leap second or two. There are several possible reasons for this change, from glacial effects to wobbles of the Earth's axis. We'll have to wait for the physics folk who study the complex place that we call home to arrive at a testable - and tested - hypothesis to know more.

4. Energy densities compared

The term energy is widely used these days... from the news to everyday conversations. What's amazing about this 'thing' is that for anything to happen anywhere - whether inside our bodies, a car, etc. - it must obey the conservation of energy. This means if one type of energy increases - say, the energy of motion of an object ("kinetic energy") - then this can only happen by either converting energy from another type already inside the object, or transferring energy to the object from someplace else. Either converting or transferring - that's it. When we start to walk across the floor our body gains kinetic energy, and in this case energy is converted from the chemical energy stored in food molecules inside our cells. (Conversely if we were pushed across the floor this energy would have been transferred to our body by the push.)

So how much energy is contained in various chemicals? One way to look at this is through their energy densities: the energy released per mass of a chemical undergoing a normal, everyday, reaction (see a graph for common chemicals here, with energy density plotted along the x-axis). Hydrogen - whether gas or liquid - tops the list at ~140 MJ/kg; it burns to water and is really light. Next at ~50 MJ/kg are hydrocarbons containing only carbon and hydrogen; they burn to carbon dioxide and water and their constituent elements are still pretty light. The third clump at ~20 MJ/kg are hydrocarbons that also contain oxygen; they also burn to carbon dioxide and water, but bring some oxygen atoms along which increases their mass. Today's batteries, meanwhile, although improving, bring up the rear at just shy of 1 MJ/kg.

So with the energy stored per kg by hydrocarbons such as gasoline being 50-60 times greater than that stored by batteries, it'll take a while (if ever) before we can fully replace the former by the latter. Keep an eye on new developments though, and continue learning about science - for human ingenuity (unlike energy :) is limitless.

3. The connection between mind and movement

Ever wondered why trees don't have brains? Or which single study tip might be most helpful? The answers, respectively, can be found in the talks here and here, and together they convey some amazing benefits from haptic learning.

2. Trig nomenclature

Why are sin, cos and tan named as they are? Matthew Conlen explains all.

1. Curiosity, and what is 'right' anyway?

Why in math and science do we so often adopt 'x' as the unknown...? Terry Moore explains.

This cartoon by Angela Melick nicely illustrates how almost every statement (and thus model) in science can be both 'right' - useful and correct for the intended purpose - and also 'wrong'. In science, as in life, context is everything.

Physics posts

6. Boiling water with or without added salt...

Predicting the outcome of an experiment can sometimes be challenging, and this is often the case when different effects work against each other. Consider adding salt to a fixed amount of water, and wondering whether this would decrease or increase the time it takes to bring it to a boil.

If we treat the container to be closed (so with negligible evaporation), then three effects occur due to adding the salt: Effect 1 - we are adding some mass to the system, and this alone would increase the time taken to boil. Effect II - we are raising the boiling point of the water, and this would also increase the time taken to boil. Effect III - we are changing the heat capacity of the liquid (with its slightly-increased mass), and in fact here the heat capacity decreases, so would alone decrease the time taken to boil.

To see which of these effects: 1 & 2 together, or 3, wins, we need to know the size of each effect. The parameters of interest can be found in Question 4 of the 2023-2024 Thermal Physics midterm posted here. Here we explore a solution with the same salinity as sea water, but the overall conclusion applies also to solutions typically used in cooking.

5. How many types of energy are there?

The previous science snippet introduced the idea of conservation of energy: that for anything to happen anywhere - which always means a change of some type of energy inside a system - then this energy must either be converted from (or to) another type of energy in the system, or transferred to (or from) the system from outside. This is powerful - nothing at all can happen, anywhere in the universe, without it being approved by the 'energy auditors'.

So how many types of energy are there? A web search gives answers ranging from "The 9 types of energy", through "The 7 types of energy" to "The two types of energy". Help!

Well, in science, as in life, the right answer (the most useful and most appropriate) depends on who we're communicating with. So for science-minded folk... nature has only two types of energy: a) energy due to the movement of objects or particles (kinetic energy), and b) energy due to forces between objects or particles (these provide potential energy). A correct answer, therefore, is two. (I am neglecting the cosmos and its still-to-be-figured-out dark energy.)

So what then is 'chemical energy'? Or 'nuclear energy'? Or 'sound energy'...?

Amazingly, each of these energies are made up from only kinetic and potential energies, but are generally due to microscopic constituents. For example, take chemical energy. We may recall from my last post that 1 kg of hydrogen gas releases about 140 MJ of energy when it burns in air.

So the kinetic energy of all the electrons and nuclei in unburnt hydrogen and unreacted oxygen added to the potential energy due to all forces between these electrons and nuclei give the initial energy of the reactants (the unburnt hydrogen and unreacted oxygen).

Similarly, the kinetic energy of all the electrons and nuclei in the water that is formed, assuming it is at room temperature, added to the potential energy due to forces between these electrons and nuclei gives the final energy of the product (the water).

The difference between these two energies - allowing also for any change in these energies due to this reaction happening at atmospheric pressure (that is, any necessary expansion/contraction of reactant/product gases) - is the energy released as heat. For ease we often call this a release of 'chemical energy', even though it actually derives only from differences in many kinetic and potential energies.

So, in nature there are only two types of energy: kinetic energy and potential energy. We humans find it convenient to lump these into packages. To package or not is up to you - the conservation of energy (provided everything is included) will hold either way.

4. What vectors are (and aren't)

A common entity we often encounter when doing science to make useful predictions is the vector. We may recall that this 'thing' has a magnitude (with appropriate units) and a direction. So, for example, velocity is a vector (the wind might be travelling at 3 m/s in a direction due-north, or at 12 m/s in a south-west direction), as is, for example, electric field (a field of 4 N/C pointing to the north, or 12 N/C pointing south-westerly). Note that 1 N/C is 1 V/m, so either N/C or V/m work ok here.

Anyway, what's great about vectors is that while they have magnitude (with units) and direction, they do not have a location. So you can draw/place them anywhere you wish. You may have already known this - perhaps you've been adding vectors by doing tail-to-tip additions and figuring out what final vector you end up with. So you're used to moving vectors around the page until the tail of one connects with the tip of another. You preserved the magnitudes and directions (so the vectors were unchanged), but happily changed their locations. As we often find in science, it's useful to know what something is, as well as what it's not.

3. Dimensions revisited

In the last physics post I mentioned that expressions within sine, cosine, and tangent operations have no physiclal units. More generally, for any formula in science we can only meaningfully add or subtract terms with the same units - for example, we can add kg to kg to kg..., but never, say, kg to s2 to m3. So, no matter how complicated a formula may be, the physical dimensions of all terms that are added or subtracted must be the same. Knowing this can help a lot!

2. Dimensions and trig formulae

Considering sin, cos, and tan... it's helpful to remember that any expression within these operations must be dimensionless. Each one can be represented by a power series, and there's no law of nature that allows us to meaningfully add, for example, kg to kg2 to kg3..., etc. Thus, no matter how complicated an expression is within a sine, cosine, or tangent, it must have no physical dimensions. Knowing this can save time and possible hiccups with the algebra!

1. Why study physics?

For you:

- excitement of doing something intellectually stimulating... learning something new each day

- accomplishment of solving problems... satisfaction from doing/building/understanding it

- the international nature of the subject... physics societies exist in almost every country around the world

- every event in nature is due to physical interactions... it's fun to identify, understand, and then harness these in a beneficial way.

For employers/wider society - physics graduates can:

- understand and parse complicated concepts

- communicate complex processes and results to a wide audience

- collect and analyse large data sets

- employ many distinct experimental and mathematical tools, while remain open to learning more

Hear about some benefits that derive from physics-based thinking, articulated by Elon Musk in 2013 here (from ~18 min onwards). Also check out the Canadian Association of Physicists site for careers that physics can lead to.